The locals fishing at the Wharry and along the coastline did so for pleasure therefore much of the equipment used was often made from what was available.

Different locations i.e. beach, rocks, cliffs, boats required different methods of fishing.

On this page Derek Wilson will look at the methods and equipment used before they are lost from living memory.

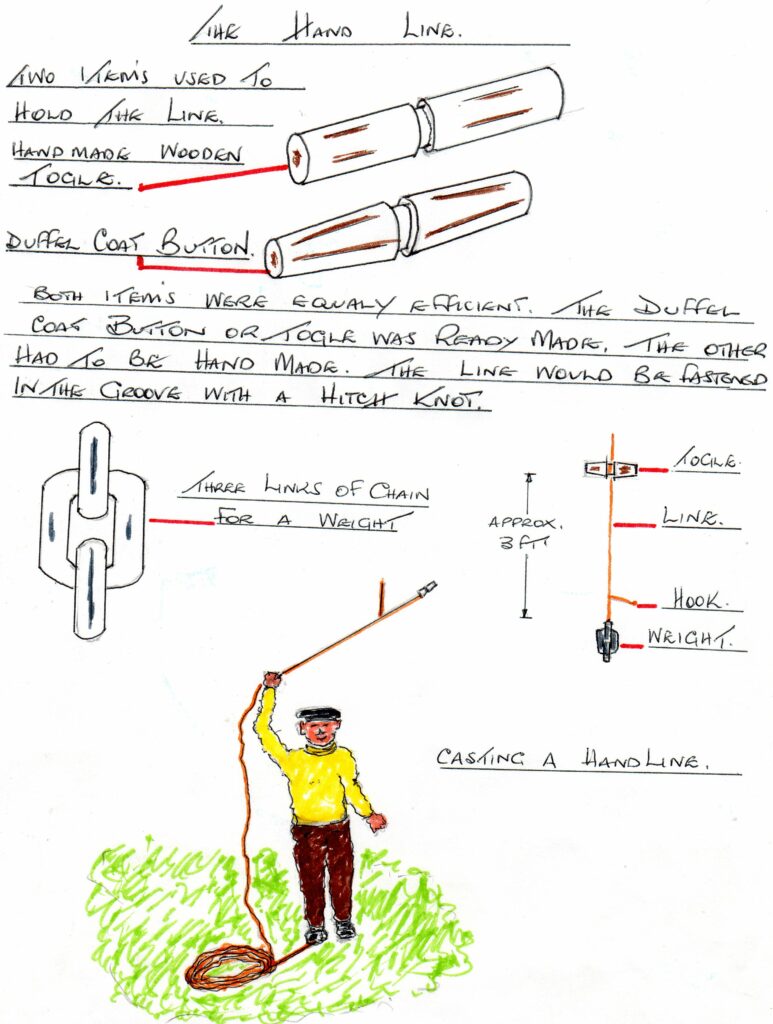

Hand-Lines

Today fishing off the shoreline with splendid carbon fibre fishing rods and hi-tec reels is a far cry from what was once used when hand-lines were the order of the day.

Hand-lines consisted of an eight inch wooden stick with about 60 yards of line (nylon twine) wound around in a criss-cross manner. One end of the line was weighted with 3 links of one inch chain. Two feet up the line from the chain a trace and hook were attached. The trace would be kept short to avoid accidents when the line was cast out. Five feet up the line from the chain a piece of wood two inches long and half an inch wide would be fastened into the line with a hitch knot (duffle coat toggles were regularly used).

For bait we used either peeler crab, lugworm, ragworm or mussels. If crab or mussels were being used these would be tied to the hook using thread (in earlier days sheeps wool was used).

When casting out, a length of line was carefully laid out in coils. The fisherman would place a foot on the end of the line and then the chain end would be swung above the head, by holding the wooden toggle with two fingers. When the correct momentum was reached the line would be cast sending it upwards and outwards.

Cod, coalies and whiting were all caught using this method.

The last two people I saw using the handline were Billy Preston and Ken Brennen both fished at the Wharry regularly.

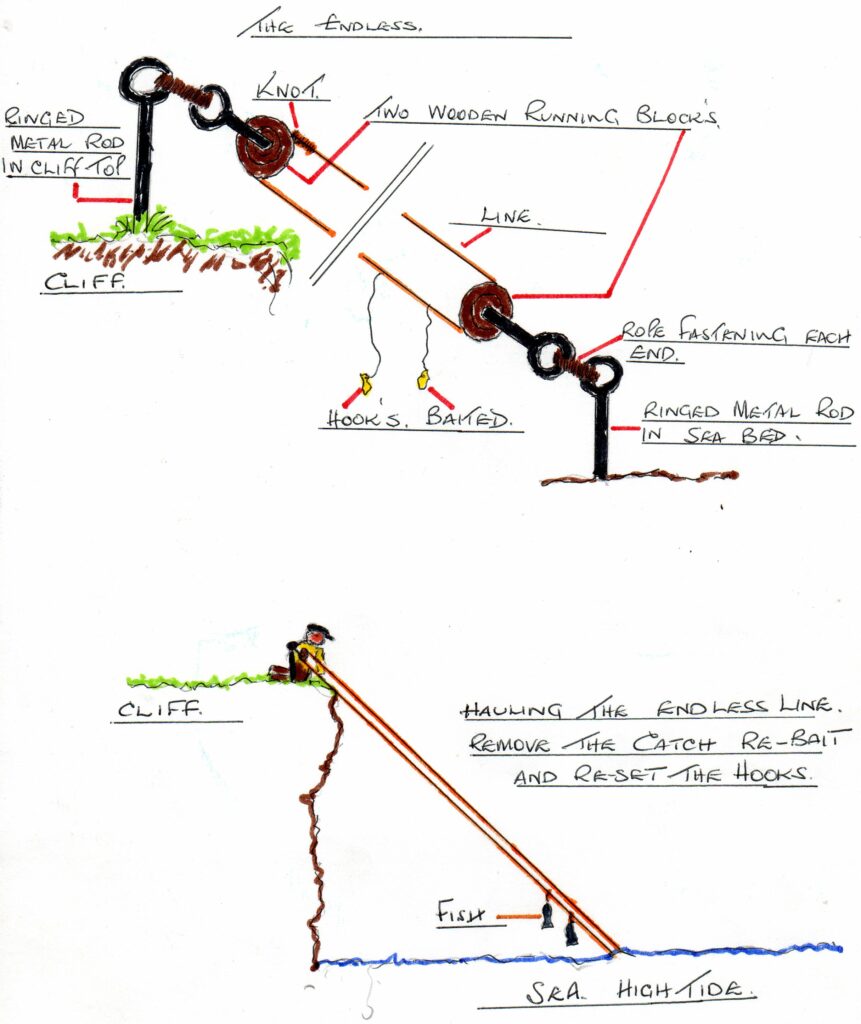

The Endless.

It`s said that Mr. Kirton of Marsden Village had a unique method of fishing, and it was named the “ENDLESS”. This consisted of a metal stake or rod with a ring on the end (made in the blacksmith’s shop at the Colliery) being hammered into the sea bed, as near to the low water mark as possible. The same would be hammered into the cliff top. A wooden running block similar to one`s used on sailing boats would be attached to each rod. A line would be threaded through the wooden wheels of the blocks and joined.

Usually two hooks with traces approximately three feet long would be fastened to the line and baited. The line would be pulled at one side lowering the baited hooks. When the joining knot or splice reached the top the fisherman knew the hooks were on the sea bed. The line could be hauled in, catch removed, the hooks re-baited and lowered into place without going onto the beach. I myself did not see the endless in use but was assured by his son Bill that it was true.

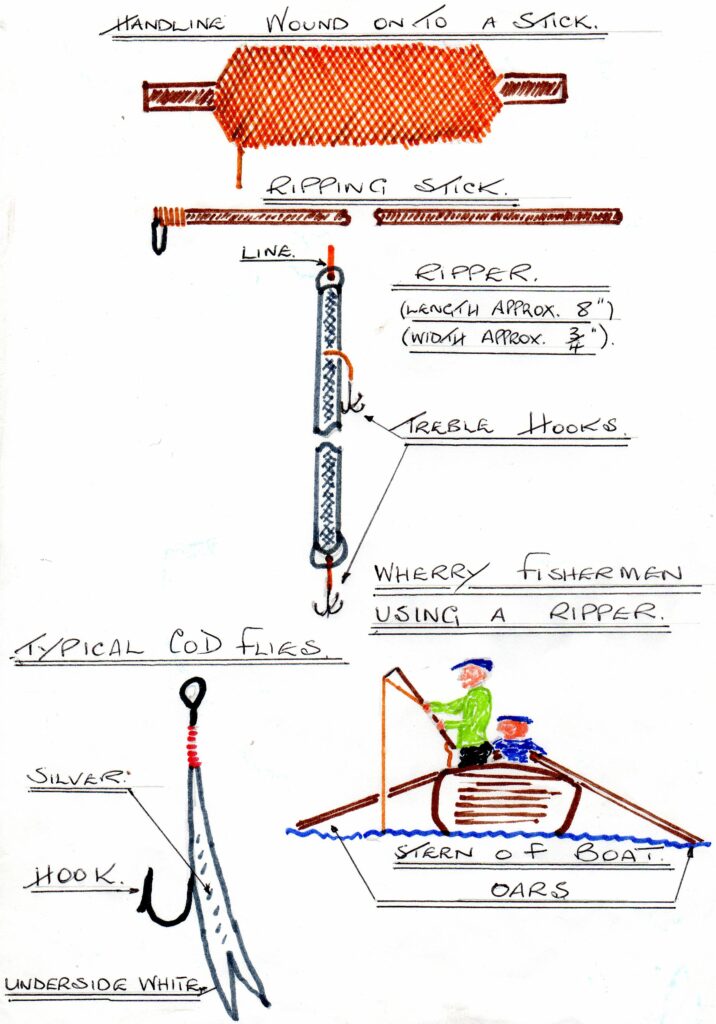

Boat Fishing

When I fished at the Wharry the most popular method of fishing for cod was the “Ripper”. This piece of equipment looked barbaric. It was a length of lead or a piece of pram handle filled with lead approximately eight inches long. A hole was drilled in each end; the line was then fastened to one end and a set of treble hooks to the other. On occasions a second set of treble hooks was attached half way along.

The fishermen had special landmarks to direct them to a favourite fishing ground, for example we would go north until we were in line with the red brick drain and then go out to sea until we lined up with the end of South Shields pier. The boat would then be positioned according to the tide run. If the tide was running south, we rowed the boat fifty yards north of the mark and allowed it to drift to and across the mark with the man on the oars slowing the boat down. If the tide was running north then the reverse happened. The person doing the ripping would then lower the Ripper to the sea bed, then raise it approximately four feet then would keep repeating this raising and lowering action giving the ripper the impression of looking like a small fish or sprat. This up and down movement attracted the cod. When the boat had drifted past the mark the ripper was pulled into the boat any fish caught would be unhooked, and the boat would be rowed back and the whole process would start again.

Reputedly one of the best exponents of this method was Walter Cauwood. Walter often fished alone, but always came in with a good catch. Another man that fished alone was Ted Stephenson.

The most popular day for fishing was Sunday. The boats usually all left the Wharry at the same time about six in the morning and would returned 4 or 5 hours later between 10am and 11 am. The locals would come down to buy the fish and help pulling the boats up the beach.

Using a Ripper was not easy work, sometimes just a weighted hook and line would be used.

The line would be baited with either lugworm, ragworm, peeler crab, mussel or mackerel strips.

Using this method both men would be seated and the boat either anchored or allowed to drift on the tide.

Mackerel fishing was great fun, attached to the line was six mackerel flies. They were made from brightly coloured material and slightly smaller hooks than cod flies. The line would be lowered to the sea bed then raised approximately five feet, the line was raised and lowered to give the flies the appearance of sprats or sile. Mackerel swim in shoals so it was not uncommon to catch three, four or five at a time. Some mackerel was taken home to eat, some given to neighbours but most was used for lobster pot bait.

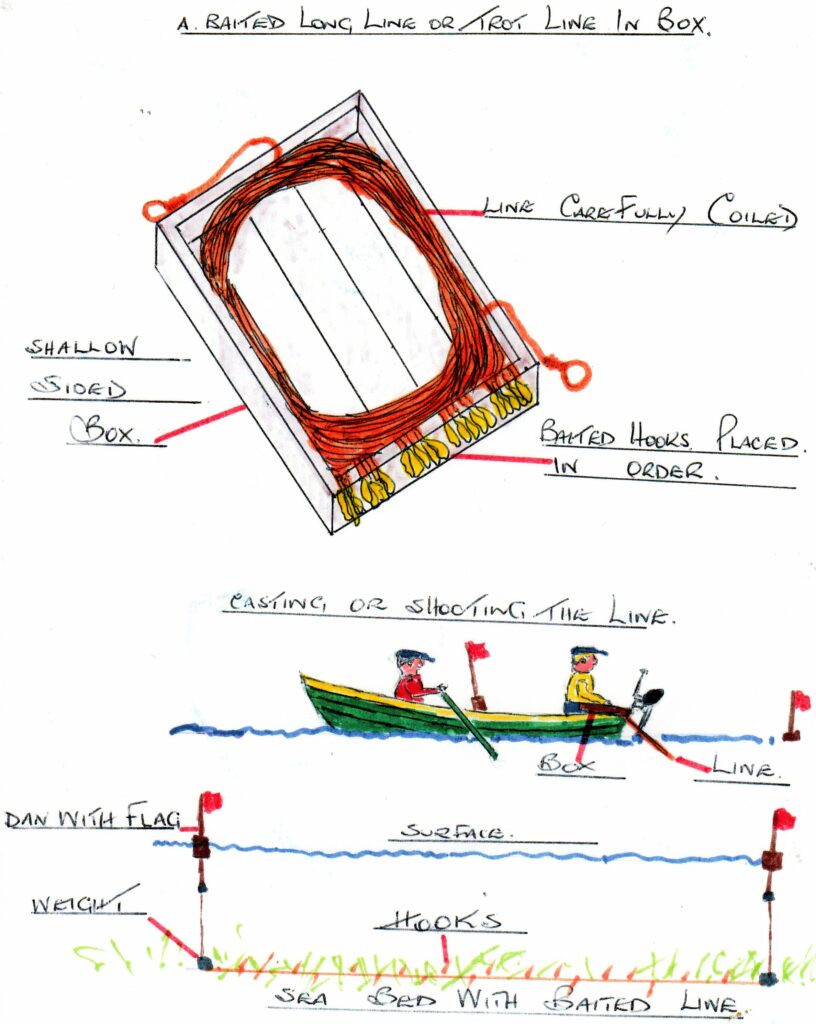

Longline or Trotline was used in winter.

Longlines were mostly used in the winter. The line would be approximately 100 yds long with 50 or 60 baited hooks attached. The bait usually mussel that had been left in a jar of salted water to harden off. Another bait used was parp. This is a creature which attached itself to rocks on gravel areas of the beach. The shore side of White Rock was a good area for collecting parp. The reason for using parp as bait was for it’s thick texture which when sliced and placed on the hook it wasn’t easy to dislodge.

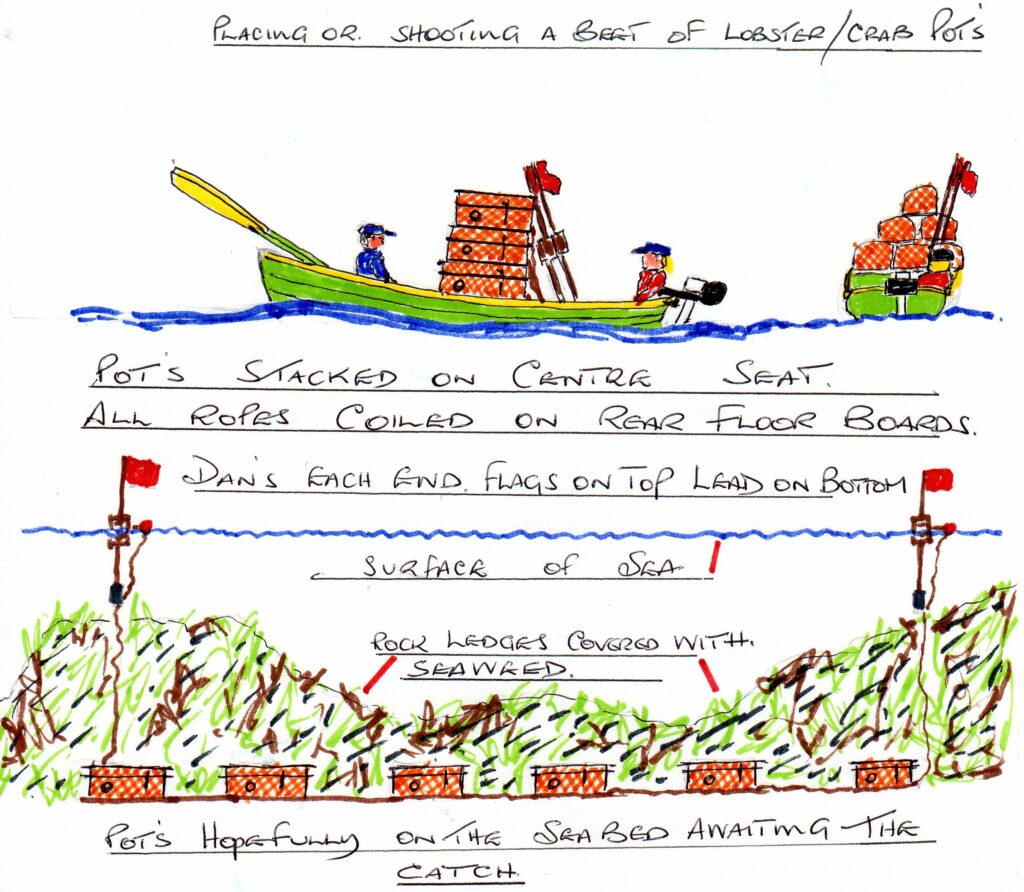

The line was placed in a box approx. 3 ft. x 2ft in carefully laid coils. The box had shallow sides and the baited hooks carefully placed in order alongside each other. The box would be placed on the rear gunnel of the boat, a dan with a flag attached would be cast into the sea. This had a length of rope attached to a heavy weight. The main line attached to the other side of the weight,no hooks were attached to the first 10 yards of line so the weight would reach the sea bed before any hooks moved from the box. The line would be carefully payed out as the boat was rowed, this was why the line and hooks had to be placed exactly in order as one mistake would cause the line to tangle.

Next morning the line would be hauled in, any fish would be removed and the line coiled into the box ready to be re-baited. Most fishermen had two long-lines one would cast before hauling the other so they always had a line fishing. ( see illustration)

Shellfish

Once again there were different methods used to catch crabs and lobsters. On the shore various gadgets were used.

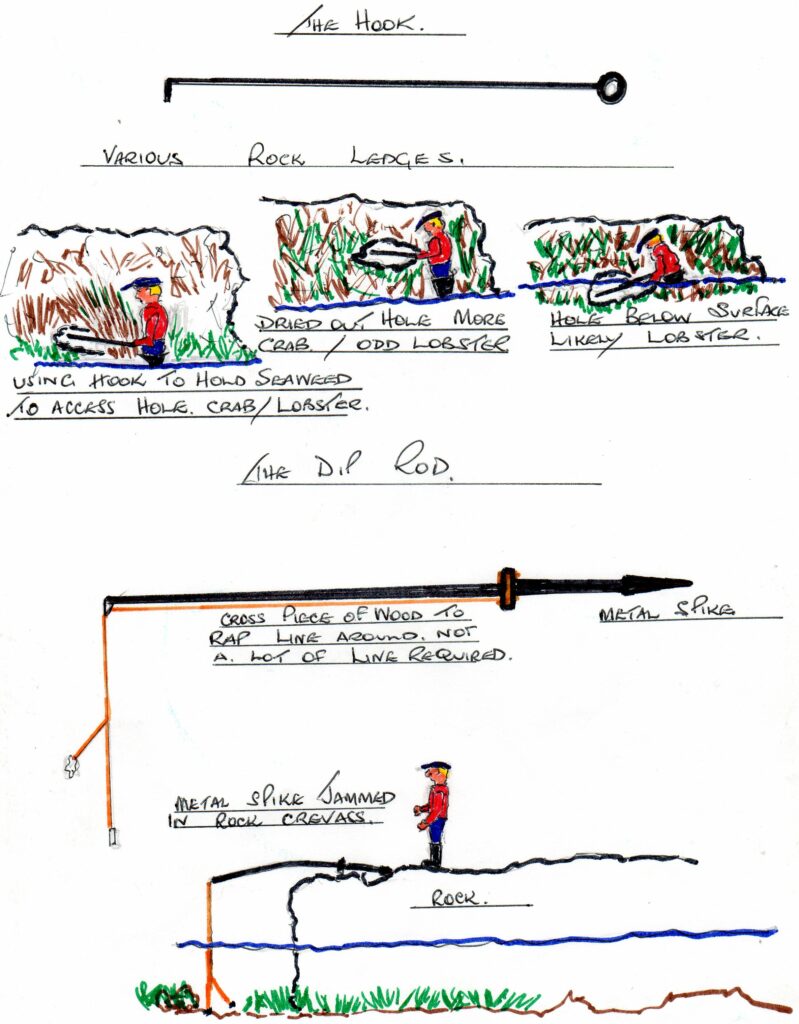

The Hook.

Hand held this was and still is a piece of quarter inch round iron bar with a 90 degree 1 inch long bend at one end, sometimes the other end was ring shaped (again these being made by the colliery blacksmith). When the tide was at low water on what is known as a big tide the hook was used to coax or pull crab`s and lobster`s from their various holes in the rocks.

When being taught how to use the hook as a young boy, my father made me aware to never put your hand in a hole to pull a crab out. Putting your hand over the top of the crab would result in the crab raising itself and jamming your hand against the top of the hole making it a very painful experience.

One of the best local fisherman with a hook is Gordon Happer whose two daughters Victoria and Rachel are now learning the trade.

The dip rod

This rod was mainly used for catching lobsters; the rod was approximately 10ft. in length, tapered from the butt end to the eye end. The butt end was fitted with a metal pointed sheath; this would be place into hole or crack in the rocks. The rod would be positioned at approximately 45 degrees and the hook baited with peeler crab or mussel or both. In the early day`s these rod`s were made from Hickory this wood being very flexible and the slightest bite could be detected. Fibre glass has now replaced the wood.

I only know of one fisherman that still uses the dip rod, Alan Chapman. A good mark for this type of fishing is the shelves of rocks exposed at low water on a big tide at the north side of Firery Bay, but you only have about 45 minutes before the tide turns.

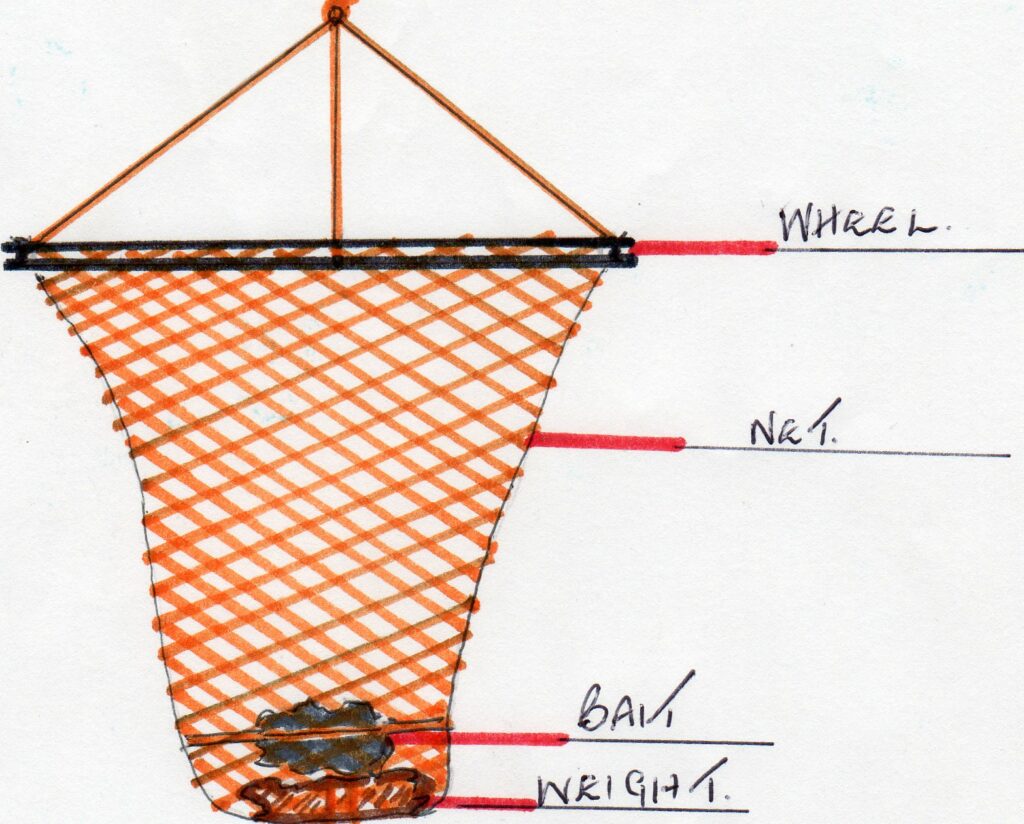

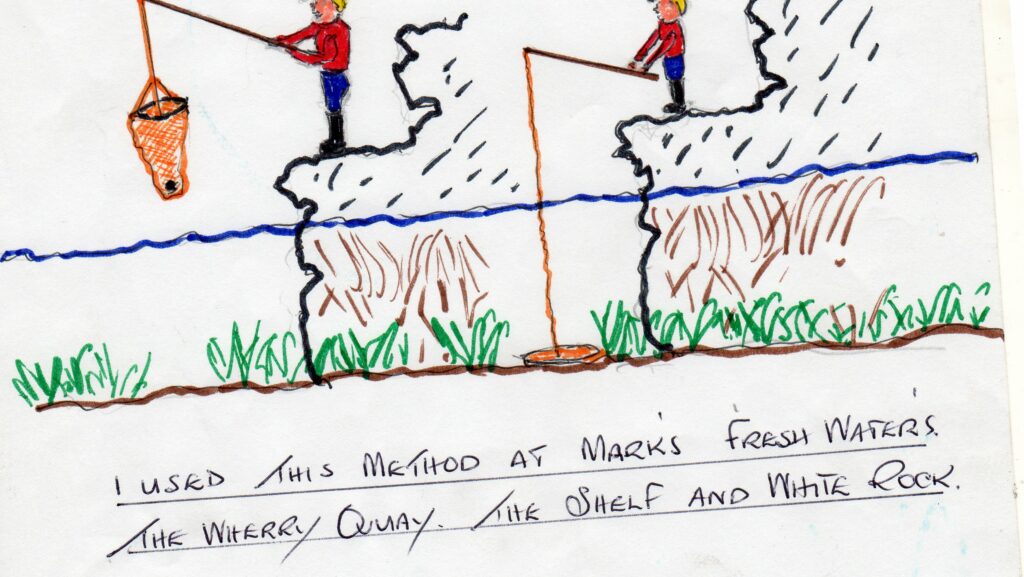

The Bike Wheel.

This method was again used for lobster fishing, a bike wheel had all the spokes removed and a one and a half inch mesh net was knitted onto the rim. It was approximately three feet in length and tapered.

Three traces were attached at equal distances around the rim, these were of equal length. They were then attached to the main line, a stone was fastened into the bottom of the net and then a herring attached as bait. The wheel is then lowered until it reaches the sea bed.

On a clear calm day any movement of lobsters etc. could be seen. The wheel would be raised quickly with the catch falling to the bottom of the net. When the water was murky we had to watch for a blob of oil coming to the surface this meant something had broken the skin on the herring. Again the wheel would be raised quickly.

Crab and Lobster Pots.

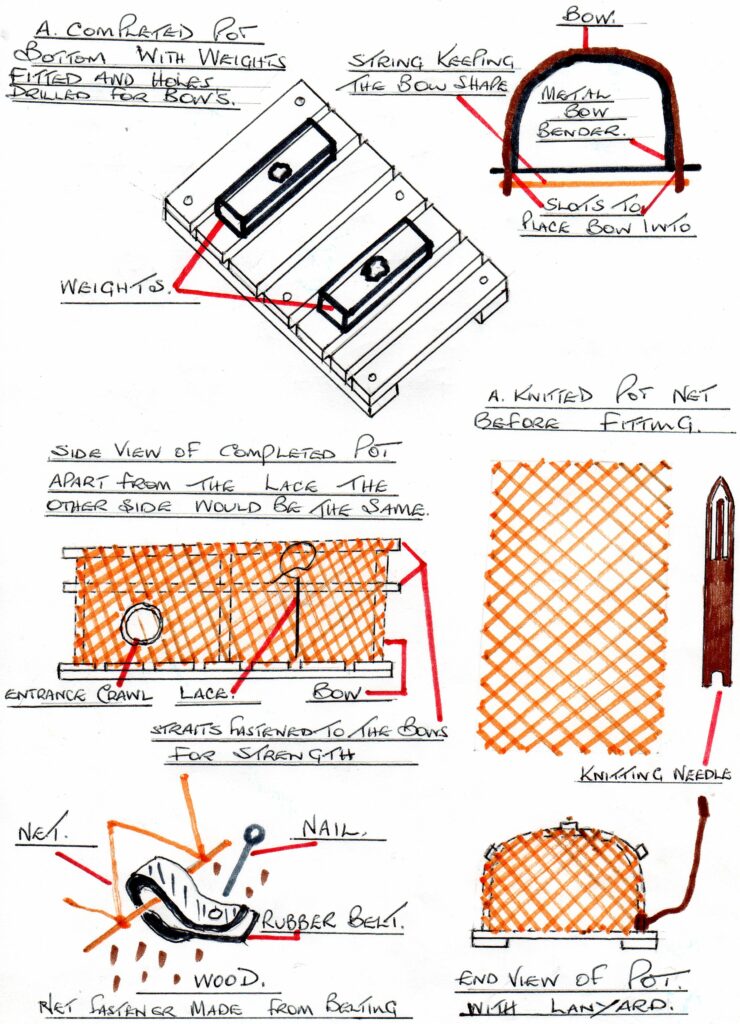

These items were made from several components. A pot bottom made from wooden lats, nailed together to make an oblong shape approximately 30” x 18”. A weight or weights were fastened to the structure, this being quite heavy as it had to sink the pot onto the seabed. The weights usually metal but could be large flat stones fastened securely to the pot bottom. Six holes were drilled into the wood to accommodate the bows. In the early days the bows would be hazel bush. They would be cut and placed in a bender (again made by the colliery blacksmith) and left to dry into shape. Later bow`s were made of solid cane then nylon pipe and now steel. There were three bow`s to every pot both ends and middle, three straights were added across the top of the bow`s.

The next stage was to make or knit the net using a special needle filled with twine. The net was created to specified size. Nowadays sheets of netting are bought and cut to the size as required. When the net was completed it would be placed over the assembled bottom with bow`s and straights fitted, the two sides of the net would be fastened onto the wood , using strips of rubber belting which was wrapped around the twine and nailed into the wood. The ends would be gathered in and both ends fastened in the same manner as the sides.

The net would now be very tight and a square of three meshes would be cut out of each side of the net (not opposite to each other ) this was to accommodate the crawls or entrances to the pot. These were a five inch tunnel which was tied across the pot. One side of the pot had six meshes cut downwards this was the door to allow the bait to be fastened in the bait string, located in the centre of the pot and also to remove any catch within. When the pot had been baited,a cod head, mackerel or gurnard usually, the door was laced up and knotted.

My boat would carry six pots comfortably so I roped the six together as one beet. If new ropes were to be used they had to be stretched and this meant exactly that, in my case tying one end to a tree and pulling on the rope every twenty metres for ten minutes each, this made the rope easier to coil.

Each beet had a dan (buoy) with a flag attached, so you could recognise your own beets by the flag. A dan was made from a pole one inch in diameter six feet in length with a cork fastened to it and weighted at the bottom so the dan stood upright in the water. A three foot long lanyard was fastened to each pot this attached the pot to the main line which made up the beet of six. Just like any method of fishing the lobster fishermen had their favourite marks. With the boat moving forward the dan was cast into the sea followed by the pots on after the other then the other dan. If the pots were new the older fishermen would tell you, “yall get nowt the morn, they`ll be singing all neet” this meant the wood would swell in the water, and in doing so made a noise, chasing the shellfish away. The pots would normally be hauled once a day, the catch removed and the pots re – baited.

The rocky grounds immediately north and south of the Wharry are excellent lobster grounds, the edible crab was plentiful in an area slightly further out to sea, where the seabed is covered with mud. Some of the boats at the Wharry were larger than my own, these boats would carry eight or ten pots in a beet.

The fishermen experimented with design of the pots to try and make them more efficient.

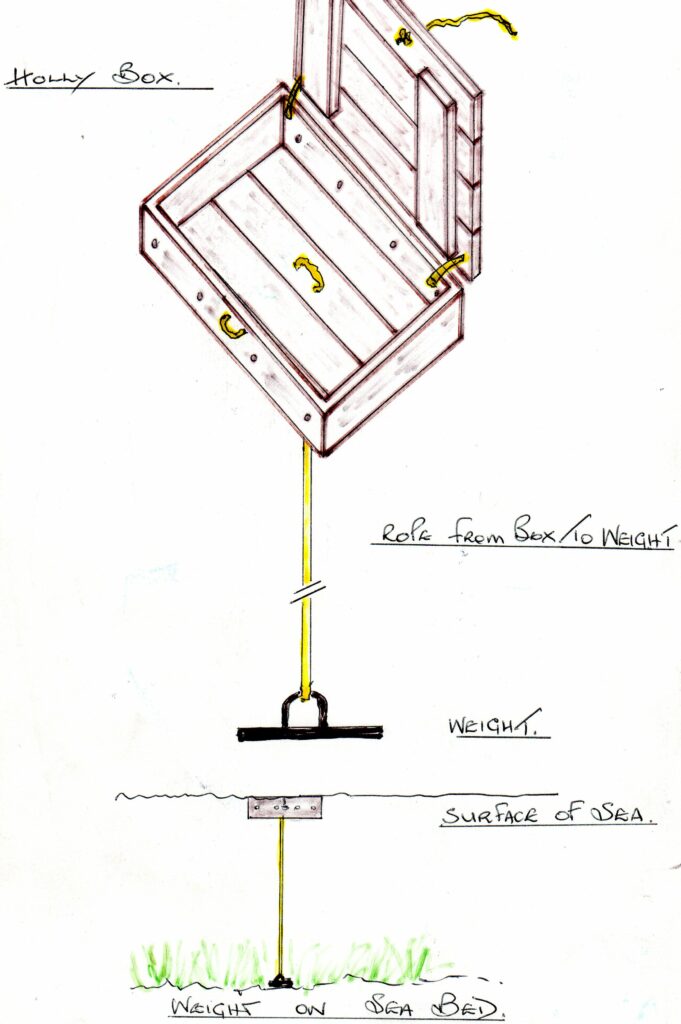

Lobsters to be sold on would be saved in a holly box. This was a wooden box three feet by two feet and six inches deep, with a rope hinged lid that was fastened with twine. The box was anchored in the Wharry causeway on a weighted rope, every day the catch would be placed in the box which kept the lobsters alive as it was slightly submerged. At the end of the week the catch would be removed and sold creating a little bit of beer money for the weekend. (see illustrations)

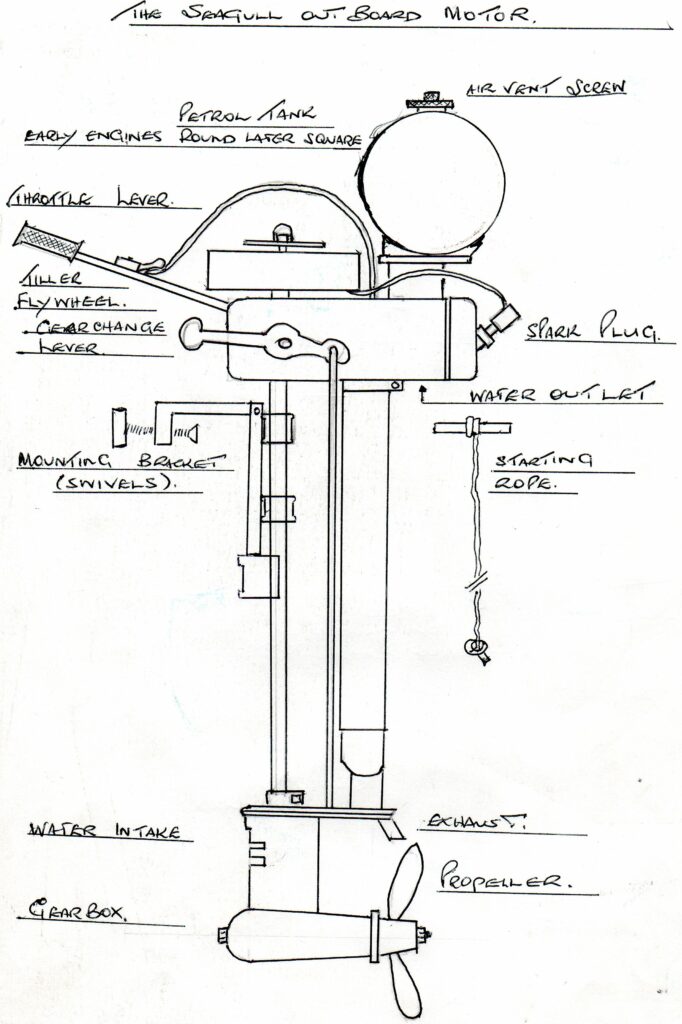

The seagull outboard motor.

The seagull was the preferred choice of outboard motor used by the fishermen at the Wherry. The engine was first manufactured at the Sunbeam motor cycle factory in Wolverhampton In 1931. These outboards revolutionised inshore fishing, the boats could now get to and from the marks much more quickly, giving more time for fishing. Beets of pots could be taken and dropped further afield.

The engine although not the fastest was very reliable, easily mounted onto boats and light to carry. One local fisherman Robert Ramsey still remembers when his father Robert Senior, who fished from the Wharry sending him to our family run petrol station for a gallon of petrol and a pint of oil. This was the mixture the seagull ran on. Early engines had a round fuel tank made of brass. The later ones were fitted with steel flat tanks. Sadly seagulls were stopped being produced in 1996, however spare parts are still available.

For advice, information, spare parts and a free forum this web site may interest seagull enthusiasts.

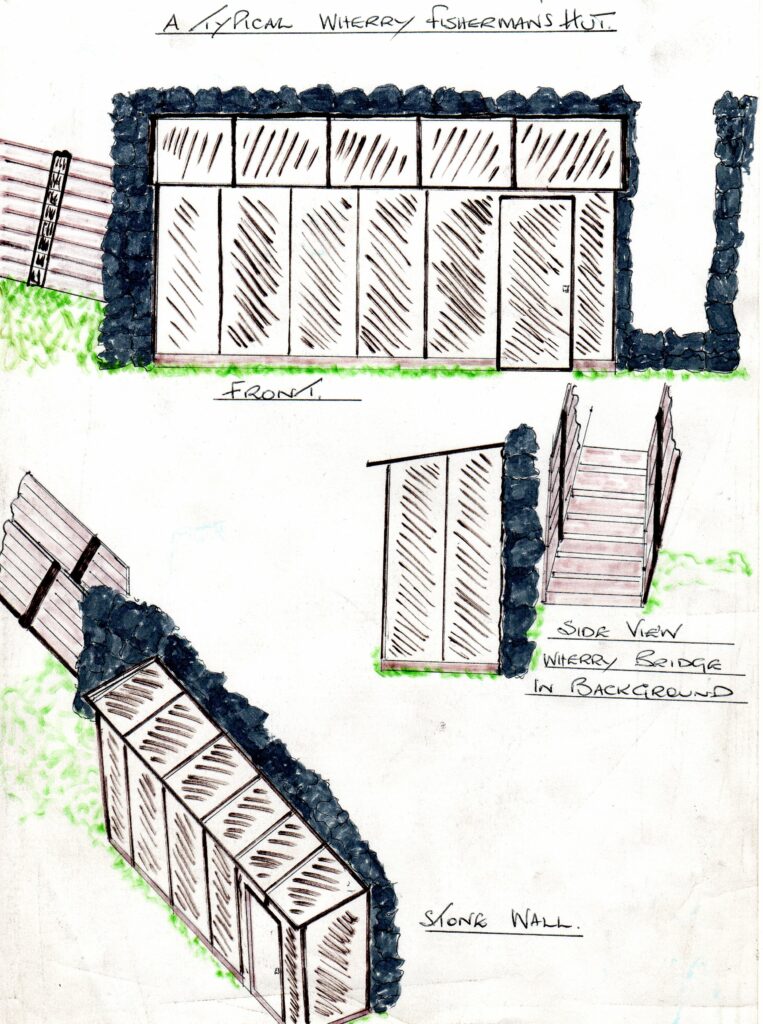

The Wherry fishermens huts.

Men fishing at the Wharry constructed their fishing huts out of materials that never made it down the mine but found its way from the pit yard to the Wharry.

The old boundary wall for the colliery ran through the Wharry and the fisherman used this wall as the back or side wall of their construction.

A simple wooden frame was constructed and fastened to the old boundary wall. This was then covered with old tongue and groove flooring or a similar material.

A doorway was then cut in and a door constructed.

The whole structure was then covered in conveyor belting to strengthen and weatherproof it.

Locks for the huts were of course made in the colliery blacksmith shop. The locks were made to different designs; therefore keys were all shapes and sizes. Square, triangle, L shape, T shape, hexagonal etc.

The fisherman stored all their fishing tackle in the huts, spare oars, nets, ropes, outboard motors etc.

Although the huts contained valuable equipment very little theft or vandalism took place, this was probably due to there always somebody being around and the toughness of the huts construction.

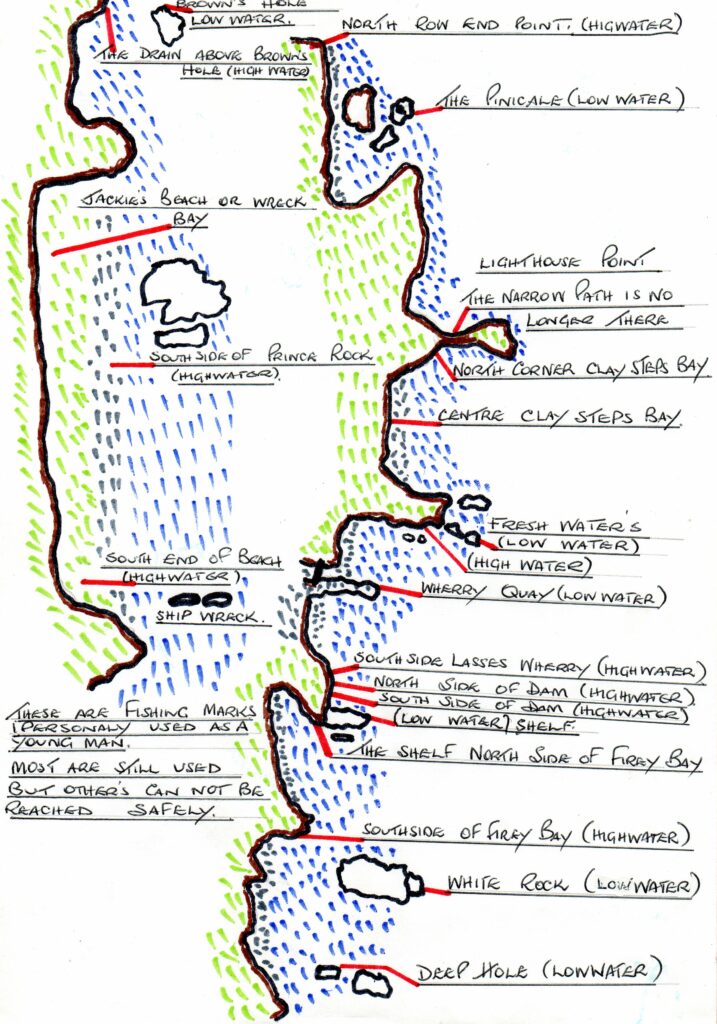

Although there is still some good fishing marks or spots within a mile North and South of

the Wharry, I would like to list the marks that I personally fished.

1. North Row End or Lizard Point (highwater)

2. The Pinacle or Black Rock Colliery Beach (lowwater)

3. Lighthouse Point (this was a large rock which had a narrow path joining it to the main cliff) the path had fallen away before my time. I fished from the cliffs directly inside the rock.(highwater)

4. North corner of Clay Steps Bay (highwater)

5. Centre of Clay Steps Bay (highwater)

6. Freshwaters northern point of the Wherry bay from cliff top (highwater) from lower rocks ( low water).

7. Wharry Quay shelf of rock south side of Wharry beach (low water).

8. Southside of Lasses Wharry cliff top (highwater).

9. North side of Dam (highwater) South side of Dam (highwater)

10. The Shelf. North side of Firery bay (highwater) lower rock shelves (low water). South side of Firery bay cliff top ( highwater).

11. White Rock ( low water) limited time on this mark due to rising tide.

12. Deep Hole North of the former Rifle Range boundary flag (low water).

13. Browns Hole North of Jackies Beach (low water)

14. Browns Hole North of Jackies Beach south side of Drain (highwater)

15. Jackies Beach Southside of Prince Rock (highwater)

16. Jackies Beach South end of Beach (highwater)

These marks are the ones I personally liked to fish, of course there are more marks between, the Grotto and Whitburn Bents. (see illustrations)

January 1996.

One Sunday in January 1996 local angler Alan Chapman was fishing the White rock mark at low water.

Alan is one of the best sea anglers on this stretch of coastline however he never expected the outcome this particular Sunday afternoon produced. Using a mixture of lugworm and peeler crab he felt a good bite on his line. Alan proceeded to reel the fish in and immediately realised it was a big fish. As he battled to get the fish in close, his experience told him it was no use trying to lift it onto the rock as he was liable to lose it due to its weight. So he walked the fish down a channel at the side of the rock until the water became shallow enough for him to step down and handle the fish which was a large cod.

The time was now approximately 1.30pm and luckily for Alan members of South Shields Angling Club were holding a club competition near by. Some of their members helped Alan move the fish from the beach and took them both to their club house where the fish was weighed and verified at 28lbs 8ozs.

Although I can’t be sure whether there has ever been a bigger shore caught cod in our area, I have never been told of one. So as far as I’m concerned Alan`s catch is the biggest.

I’ve now reached the end of my memories of fishing at Wharry. I hope whoever reads these accounts has gained some insight into the ways we used to fish in the past and the enjoyment I had being a Wharry fisherman.

Derek Wilson

Whitburn 2014

Final word;

Photo my grandson Luke aged seven, the sixth generation of the Wilson family to fish at the Wharry

Copyright © 2013 Marsden Banner Group.

All rights reserved. Permission granted to reproduce for educational use only (please cite source).

Updated 2018