In the 19th century Marsden was still quite an isolated hamlet however it still managed to support two public houses The Marsden Grotto and The Marsden Inn.

On this page we are looking at the relationship between the Inns, the local community and the Whitburn Coal Company.

The Marsden Grotto naturally remains in its original location. Its history including that of Jack the Blaster and Peter Allen are well documented and good accounts can be found on websites such as wikipedia and such like, less so is the Marsden Inn.

However probably the most concise history of the grotto ever published is by local author Bill Greenwell. A copy of the book can be obtained direct from him. For details contact him at billgreenwell62@outlook.com

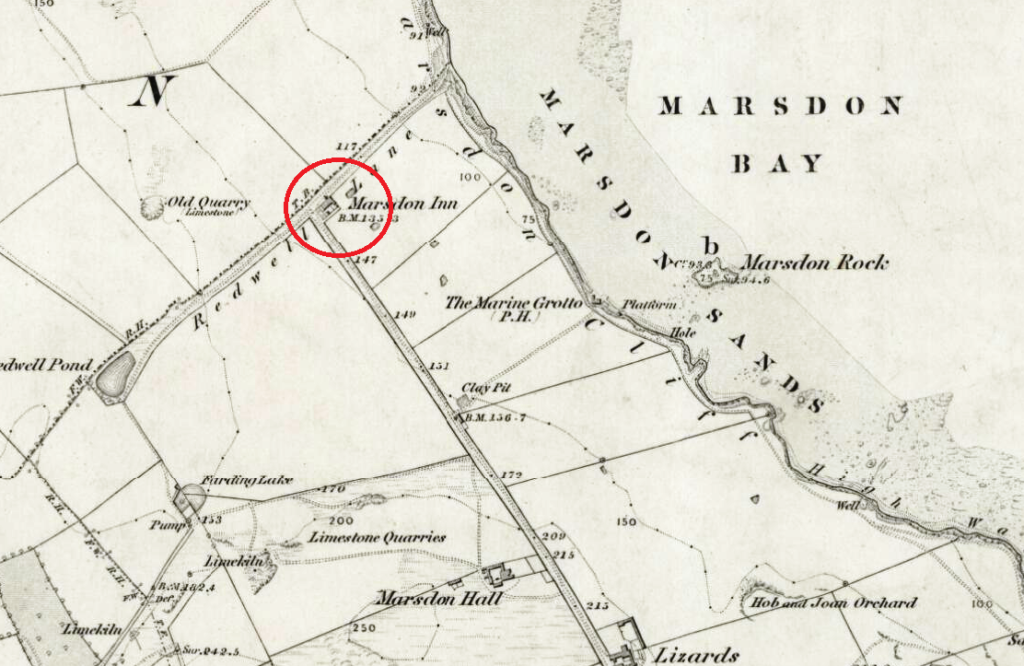

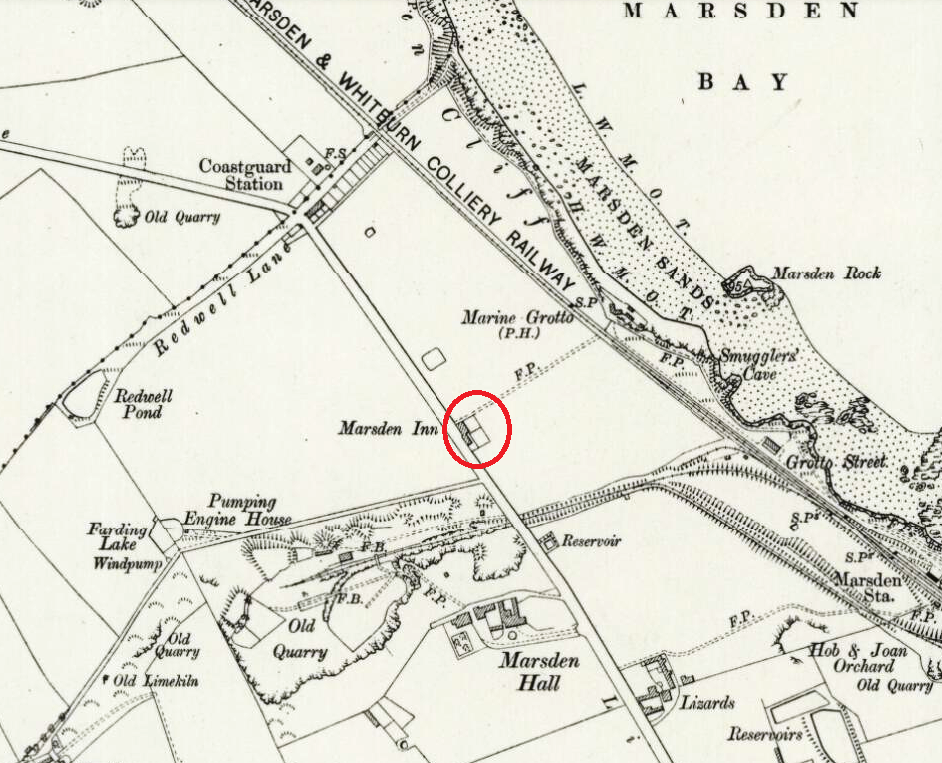

Over the years the Marsden Inn has stood in 3 different locations. In 1939 it moved to its present location on the north side of Redwell Lane.

Originally the Inn stood on south side of Redwell Lane, before moving in the mid 19th century 300 yards to the south on Lizard Lane, directly west of the Grotto.

Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Convalescent Society

The reason for the first move I believe was at the behest of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Convalescent Society. The Society was set up to provide a convalescent facility for the deserving poor following an illness or an accident.

In 1861 the Society leased the original coastguard homes that stood on the south side of Redwell Lane next to the Marsden Inn. (These coastguard homes, should not be confused with the coastguard station that was built on the north side of Redwell Lane in 1881).

At the Inauguration of the Convalescent Home in 1862 the Reverend Moody Vicar of Newcastle commented that “He hoped some allusion would be made to the fact of a public house being next door, and he would endeavour to secure funds to take it for the use of the inmates” “This would remove temptation from the friends of the patients who might visit them”.

We can only guess that the Convalescent society got their wish and took over the premises and incorporated it into the home. This would explain why the Marsden Inn moved to the south on Lizard Lane.

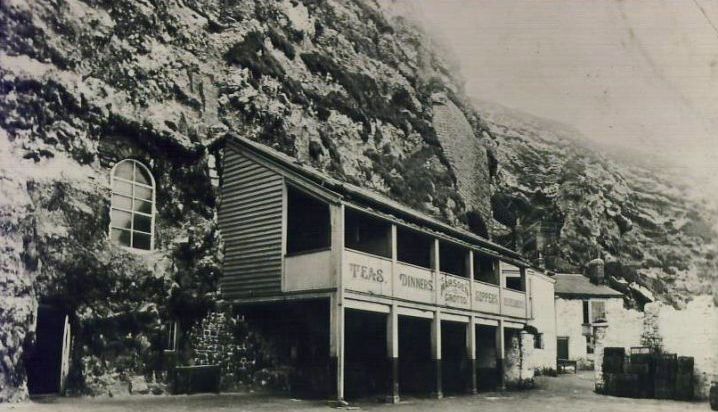

The end building on left is quite possibly the original Marsden Inn.

Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Convalescent Society ran the Marsden home for about a decade. This advert is from the Newcastle Courant Friday 11th September 1863.

Marsden was however only a temporary home whilst the society constructed a purpose built building in Whitley Bay. At the society’s annual meeting in May 1866, Dr Philipson spoke of the limitations of Marsden being so apparent he could not conclude his report without expressing his longings for the completion of the Whitley Bay home.

The Convalescent Society opened the Prudhoe Convalescent Home at Whitley Bay on the 14th September 1869 and continued to run both homes until the 1870’s before giving up the lease on Marsden. The buildings at Marsden were then converted back into private dwellings.

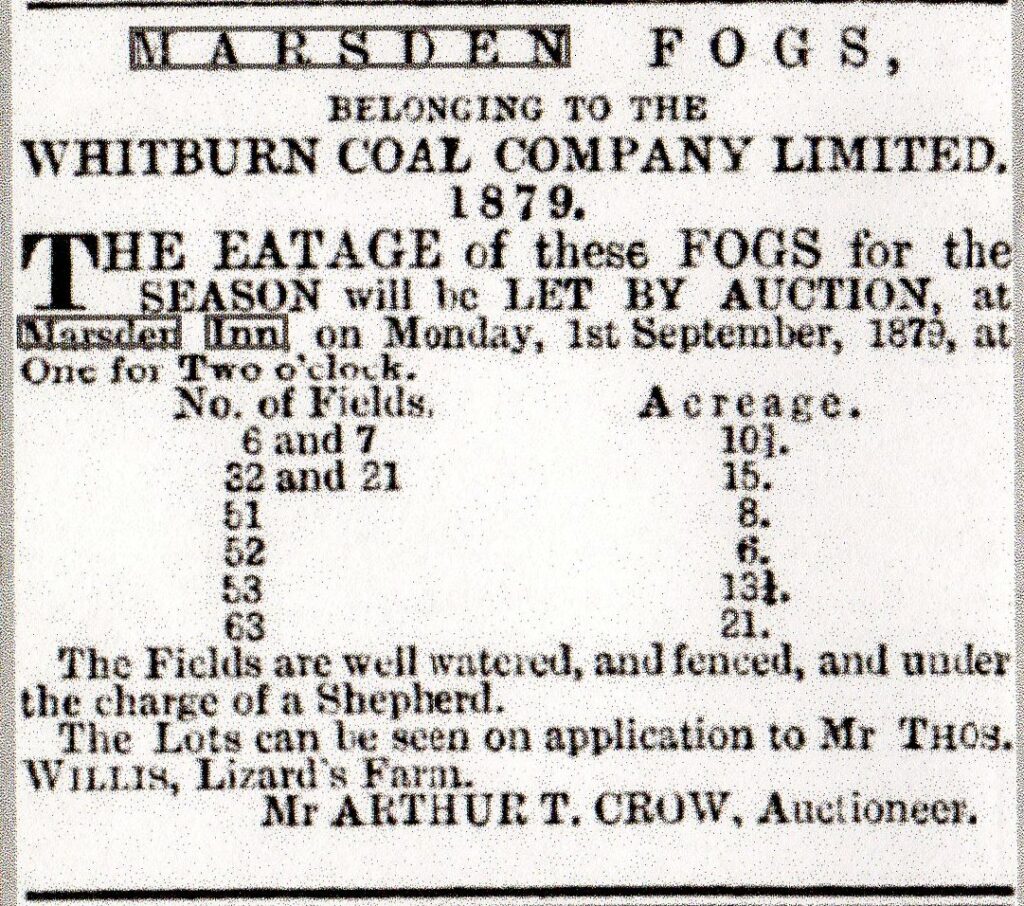

The Whitburn Coal Company

In the 1860’s the Whitburn Coal Company had started acquiring large quantities of land and buildings in and around the Marsden area in preparation for the sinking of its new coastal colliery.

To administer and manage all the acquired farms, buildings, and land the coal company set up a subsidiary called Marsden estates.

long with the sinking of the colliery the coal company started to build Marsden village. The village was always known as a temperance village as it had no pub however this had never been the coal company’s intention.

On Wednesday 1st September 1875 a report from the Brewster Sessions appeared in Shields Daily Gazette. (The Brewster Sessions was the name given to the annual meeting of the local licensing magistrates who renewed or sanctioned new licenses).

The Whitburn Coal Company was applying for a license to build a public house in Marsden village directly opposite to Souter lighthouse gates. However this application was opposed by the brethren of Trinity House who objected to a public house being placed in such close proximity to the lighthouse as could be a temptation to their “servants” to drink.

Interestingly during the application Hilton Philipson one of the partners in the Whitburn Coal Company and assisted by Mr Skidmore a barrister of law produced plans that the coal company had for the area. The plans showed that 70 houses had already been built at Marsden and that 1,000 more were to be built, as once the colliery was complete they expected to employ approximately 2,000 men.

Therefore Marsden village was only a 10th of the size the coal company had originally envisaged. Which direction the expansion was planned is not known, however before the railway and coast road were built it was a different landscape, with plenty of open land for housing.

It is possible that these plans to expand the village were abandoned due to the slow uptake for the housing that had already been built, with the men preferring to travel to and from South Shields each day. It’s understandable why the workforce would favour the relevant protection of a town in winter and what it had to offer in the way of shopping and entertainment, rather than living isolated on an exposed cliff top.

Did this decision not to extend the village mean it had always been on the Coal Company’s agenda for railway line to carry passengers as well as minerals?

Although a public house was never built at the village, it would not long be before the coal company owned the lease on 2 pubs within walking distance of the village the Marsden inn and the Grotto. It is easy to see why the coal company would want public houses with miners having the reputation of working and drinking hard. If the coal company were paying the wages what better way of getting some of that money back than by monopolising the local pub trade.

Inquests

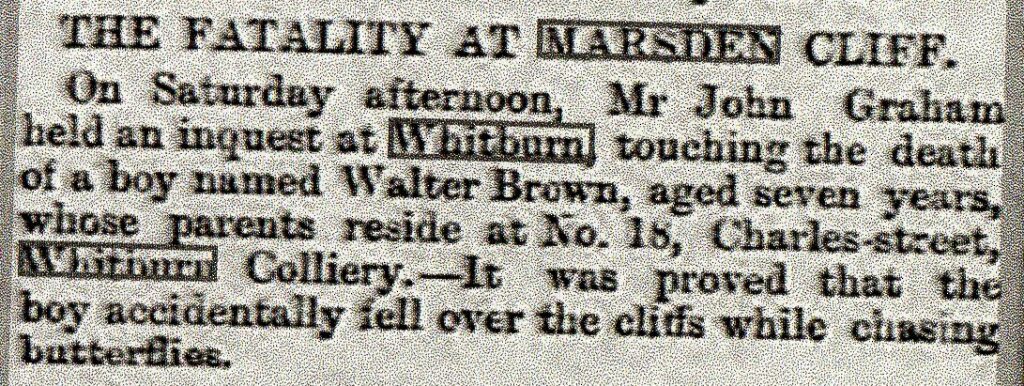

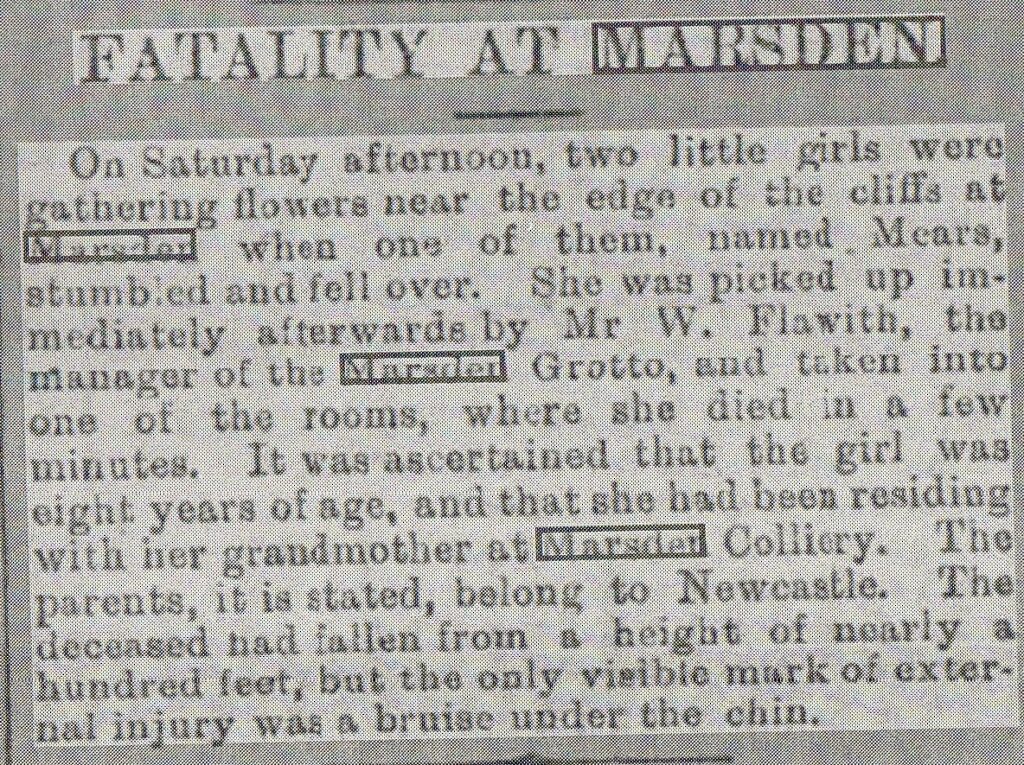

During the 19th and early 20th century despite Marsden being quite sparsely populated there were a phenomenal number of deaths occurring in the district with both the Grotto and Marsden Inn hosting coroner’s inquests.

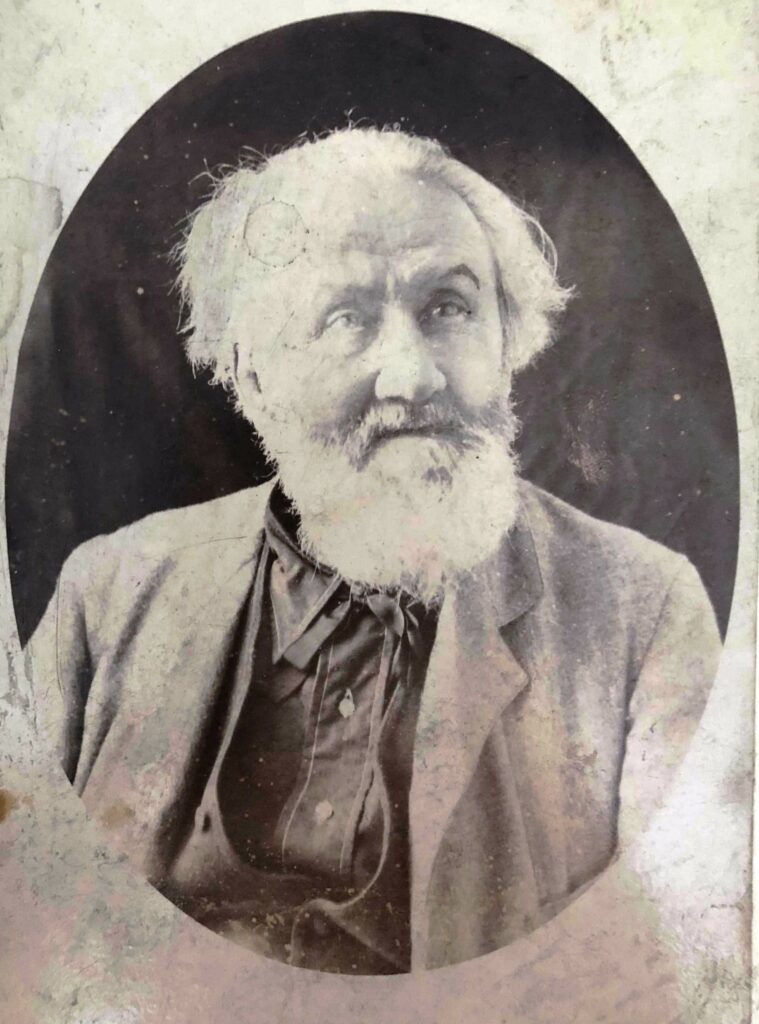

Many of these inquests were carried out by John Graham who was the county coroner for the Chester ward which covered Marsden and he was a frequent visitor to both the inns. Graham was quite a well known character; born in Sunderland in 1834 he trained as a solicitor before becoming a county coroner a post he held for many years. He had also been president of the Sunderland Law Society, president of the Royal English Arboricultural Society and was a member of both Durham and Newcastle Antiquarian Society. Graham was a man who had a social conscience and he was very sympathetic to the plight of the working classes.

Two of Graham’s most high profile inquests were The ‘Victoria Hall’ disaster of 18th June 1883 when 183 children lost their lives in Sunderland and West Stanley pit disaster of 1909 when 168 men and boys were lost.

During the West Stanley inquest Graham was perturbed that nobody knew the exact number of men and boys working underground at the time of the explosion or who they were.

At the time of West Stanley disaster some of the pits in Durham used a simple tally or token system, where each man had two metal tokens with their works number stamped on. They handed one to the banksman before entering the cage to descend the pit and one handed to the banksman when they returned to the surface this allowed the management to know who was underground at any given time. West Stanley did not use this system. So disconcerted by what he had witness Graham took it on himself to ensure every pit in the country adopted the tally system, so the identification chaos at West Stanley could not happen again.

Most of the inquests carried out at Marsden were as you have expected involving accidents that occurred at the pit or the quarry. However a lot did involve the Marsden Rattler, drownings, unidentified bodies being washed up on the beach, and people falling or jumping off the cliffs tops. The numbers of people falling or jumping from the banks were quite significant in those days.

Many of these inquests involved children and how easily accidents occur.

During the First World War Marsden remained a dangerous place to live. You were even attacked by our own side. The following abstract is from the Newcastle Journal 14th January 1915.

‘Exciting Incident at Marsden’

Some alarm was created at Marsden yesterday owing to the dropping of a shell not far from the railway station. After a sharp whistling noise there was a heavy thud, and it was ascertained that a projectile had made its unwelcome appearance uncomfortably near the colliery village. From inquires it became apparent that the shell, which was not an explosive one, had been fired from Tynemouth to warn some approaching vessel which was not complying with the port regulations and that it had some way been deflected from its course. Striking first a railway embankment, it ultimately landed in a mound. A number of people were working in a field near the place, and naturally they got a fright, but everyone was soon reassured on the circumstances being explained. Subsequently the shell was taken change of by the military authorities.

This sad story of a brave Marsden lad is from the Newcastle Journal Saturday 30th September 1916.

Lance-Corporal W C Brown D.L.I. in a letter from France to his parents, who reside at the Marsden Grotto near South Shields. Says; “Here’s a surprise for you. I was having a tour around some of the captured trenches, and of course, had a look at some of the dug-outs. When I was going down the steps of one I happened to look up, and saw cut out on one of the rafters ‘ MARSDEN GROTTO’ You can guess my surprise. I wondered if some Marsden lad had been there and done it. I never expected to see the name of my home in a German dug-out.”

Research shows that LC William Cooper Brown’s father, Thomas was landlord of the Grotto. Sad footnote; William did not get back to Marsden, he was killed in action on the 22nd June 1917. Before going to war on the 18th October 1915 William had married Elizabeth Ann Dickinson (They could not have had much time together). Elizabeth’s family lived in North Street, Marsden Colliery, her father was a deputy at the pit.

Landlords

There have been many memorable landlords at both pubs however I am concentrating on two of them for differing reasons Sidney Milnes Hawkes and Segar Robinson.

Sidney Milnes Hawkes was a very interesting character. He was a journalist, barrister, brewer and gambler. He came from an old and wealthy Hertfordshire family. He identified himself at an early age with the revolutionary movement on the continent and was particularly friendly with “Giuseppe Mazzini” (1805– 1872), nicknamed The Beating Heart of Italy, he was an Italian politician, journalist and activist for the unification of Italy.

It is believed that Hawkes was very hands on in the Mazzini cause and undertook gun running and less savoury activities on his behalf.

Hawkes had passed his Law exams in 1841 and practiced until he turned his hand to brewing. In 1852 Hawkes purchased the Swan brewery, Walham Green, London. During his ownership he produced a brewing pamphlet to advertise the brewery, the content of which still provides researchers today with valuable insight about the brewing practises during the middle of the 19th century. In 1854 Hawkes sold his brewing business to his old friend James Stansfeld the liberal politician. Later Hawkes lost his fortune in an unlucky business venture with Stansfeld.

The 1871census shows Hawkes and his family had relocated to Marsden and were living at Marsden Villa whilst working as a journalist in Newcastle.

In 1872 the same year as the death of his friend Mazzini, Hawkes resigned his job on the newspaper and took over the lease on the Marsden Inn. Two years later in 1874 he also took over the lease of the Grotto and ran both pubs.

Hawkes knew and was friends with some of the most prominent people in the country at that time, so why he would hide himself away in this isolated spot as a pub landlord is anybody’s guess.

015 the following update on why Sidney Milnes Hawkes hid himself away in Marsden has been provided by

Dr. Allison Scardino Belzer Assistant Professor of History Armstrong State University Savannah Georgia USA.

Harkes hid himself away after a scandalous divorce! His first wife was Emilie Ashurst, daughter of the senior partner (William Ashurst) at the law firm where he worked when he finished college at the University College, London. They married on July 22, 1843. His best friend (James Stansfeld) married her sister Caroline the next year. In 1849 both Hawkes & Stansfeld left the law firm and bought the Swan Brewery and went into business together. But after 3 years in 1852 Hawkes was pushed out. It was probably to do with him starting an affair with a neighbour Emily Batson and getting her pregnant. The following year in 1853 the child was born Sidney Milnes Hawkes junior. In 1854 Hawkes deserted his wife and declared himself bankrupt and went to live in Belgium. She filed for divorce in 1859 and both of them happily remarried (he married Emily Batson whom he had been having the affair with) and he seems to have stayed on good terms with Emilie. Her family, in contrast, was not so forgiving, and he also fell out with his previous friends in the Italian fund-raising group.

Hawkes was described by a friend as being “as gentle as a girl and as amiable as an angel”

however despite his demeanour reports of the day suggest he was well liked and respected by the miners and quarrymen that patronised his licensed premises and equally disliked by the police.

During the late 19th century the Marsden Inn was the main pub frequented by the miners and quarrymen with the grotto being patronised by day trippers, curiosity seekers, artists etc. This could be due to the men not wanting to use the stairs to the Grotto after a hard days graft or perhaps they were encouraged to use the Marsden Inn rather than the Grotto.

News of the day reported in the Shields Gazette revealed bouts of drunkenness, fighting, out of hours drinking, gambling (pitch and toss) all taking place at the Marsden. Many of the claims of law breaking were being referred to the magistrates by the police. When the claims were made against his clientele it was Hawkes who disputed the police version of events.

One memorable event took place on Good Friday 7th April 1882 when police summoned Hawkes before the magistrates for keeping his house open during prohibited hours and for permitting drunkenness on his premises.

On the 19th April Hawkes appeared at the County Petty Sessions to answer the summonses. Hawkes (the barrister) conducted his own defence.

Police Sergeant Deaton gave evidence to the effect that he visited Marsden on the day in question and found that business was being carried out if it were an ordinary day. Music was being played, two men were found fighting in one of the rooms, and several parties were drunk. Quoits were also being played and there were about a thousand people in front of the Inn. Under questioning from Hawkes, Deaton admitted he and other officers had been giving Marsden a lot of attention lately. He also admitted that he occasionally went up on the rocks with a pair of opera glasses however this was not necessarily to watch Mr Hawkes pub door (laughter from the bench and within the room).

Hawkes pointed out to the bench that only one person had been summoned for drunkenness that day, and that person was arrested about half-past eight in the evening. It was a great misfortune to him that certain parties had behaved badly,but it was no disgrace to him, as had done what he could to prevent this. Hawkes admitted allowing dancing and singing on his premises but questioned if it was illegal. He was not aware it was, unless they went back to an act of Charles II which not only made singing and dancing illegal but also for a man to have a drink. Hawkes said he hardly thought the bench would trouble themselves with Charles II therefore he would leave the matter in their hands.

The bench was absent for about 10 minutes when they returned they had decided to dismiss the summonses.

In October of this year 1882 Sidney Milnes Hawkes retired as a publican selling up the Marsden Inn with the lease being taking over by the Whitburn Coal Company. His daughter continued to run the Grotto for a further couple of years until she sold up in 1885 when again the Whitburn Coal Company took over the lease.

Sidney Milnes Hawkes retired to Bruges in Belgium then later to Jersey where he died in 1905.

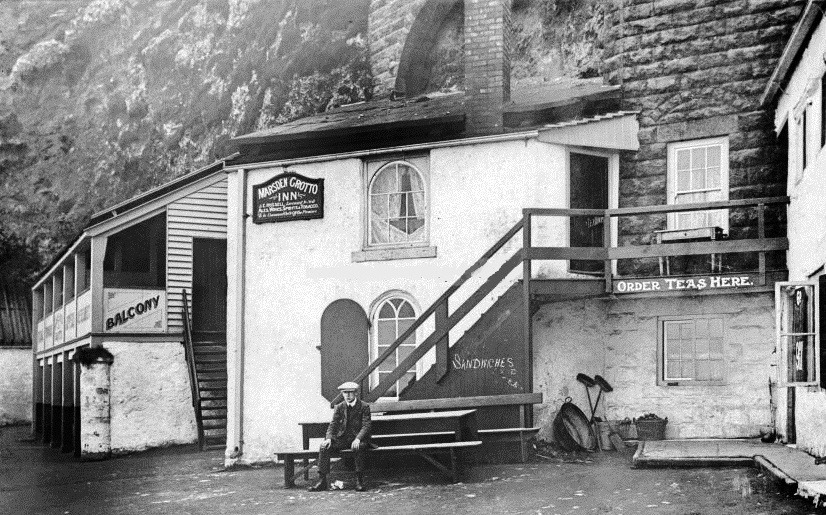

The Coal Company now had both leases and it was during this period that the Marsden Inn prospered and the Grotto was left to fall into disrepair and by the 1890’s it was only open during the summer months. Several tenants tried to revive fortunes of the Grotto without success.

In 1891 the Whitburn Coal Company was absorbed into the Harton Coal Company and they became the new owners of the Inn’s.

In 1897 the coal company installed James Robinson (Segar) as manager of the Grotto. He was a stonemason employed by the Harton Coal Company. How good of a manager he was we will never know because just a year later in 1898 Vaux breweries took over the lease from the Harton Coal Company.

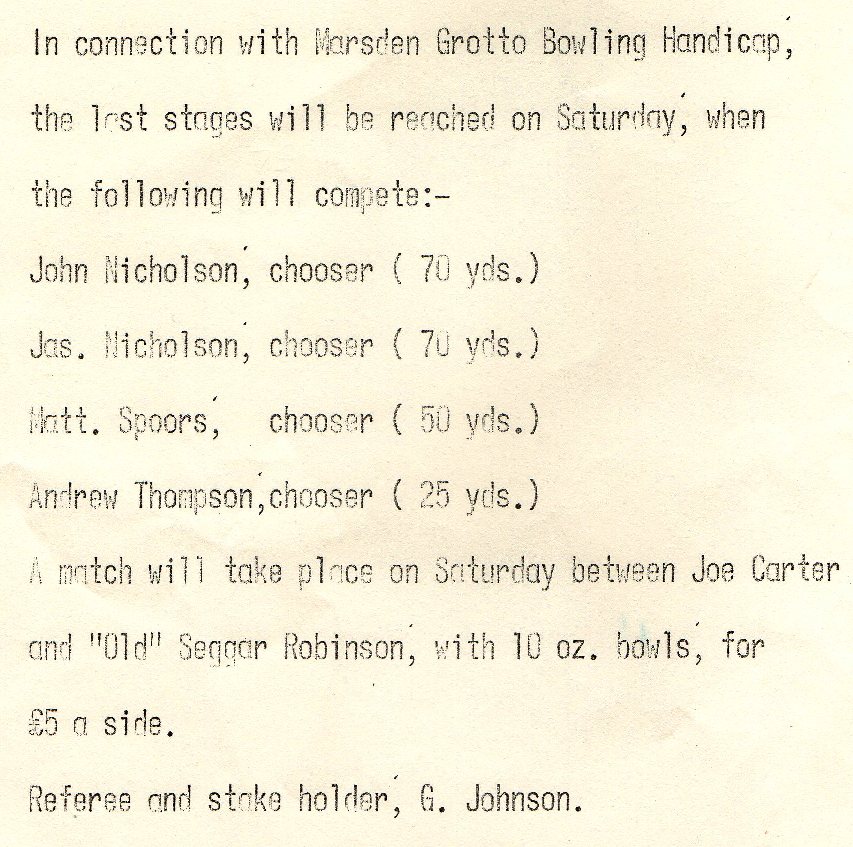

I have singled Segar out as he helps us diverse a little as he was a fine exponent of the long forgotten sport of ‘Booling’.

Bowling (sometimes called potshare bowling) was a hugely popular sport in the North East right through the 19th century and into the early 20th century. It was almost exclusively played in the mining villages of Durham and Northumberland. In its day the sport was as popular as football is today with thousands of people travelling all over the North East to watch. There appears to have been no written down rules, as the rules were just passed down from word of mouth from generation to generation. There also appears to be some slight variations in the rules from village to village.

The main aim of ‘Booling’ is to throw a stone ball over a mile course. It was played on back roads, tracks or on the sands. Two men would take turns to bowl their ball. Each bowler was assisted by a man called a ‘trigger’ who would mark where the bowl stopped by sticking a 3 foot long stick called a trig in the ground. The next throw would be taken with the ball being released when the bowler’s feet were astride the trig.The first across the finishing line is the winner. It has been described as a simple game of golf without holes or clubs.

Bowling was a handicap and the coal miners would gamble heavily on the outcome.

Inns and Innkeepers played an important role in keeping these traditional sports alive and would often promote the events.

The Grotto was no different in this and had its own handicap. This photocopy of a handbill from the turn of the 20th century shows Segar as one of the competitors.

Photos courtesy of Malcolm McKenzie

When Vaux took over the lease on the Grotto they started to clean up the area and redevelop the site to make it more popular to locals and day visitors. However the Marsden Inn remained the miner’s choice as a local. Then in the late 1930’s a seed change occurred.

Firstly in 1939 the new Marsden Inn opened where it stands today on the north side of Redwell Lane. This paved the way for the old one to be closed down.

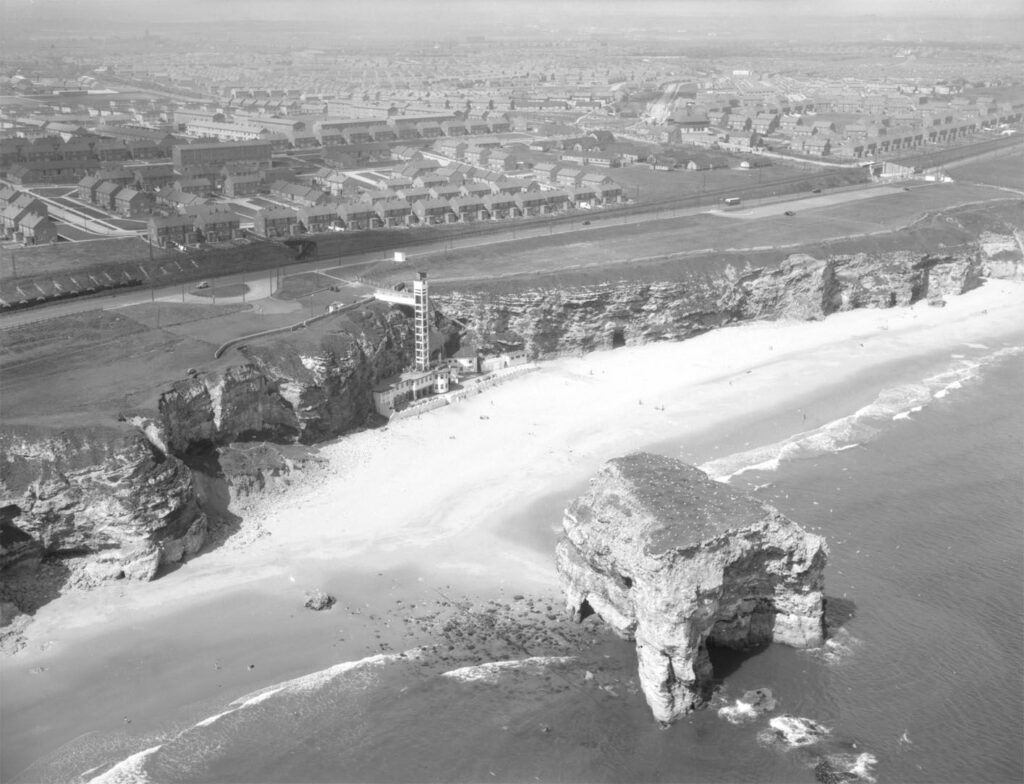

In 1938 Vaux had won planning permission to install an electric passenger lift to ferry patrons up and down the cliff face.

It was now time for the Grotto to be the miner’s pub of choice. It became the closest pub within walking distance of Marsden Village and with the installation of the lift, now the men did not have to walk up and down stairs after a hard days graft.

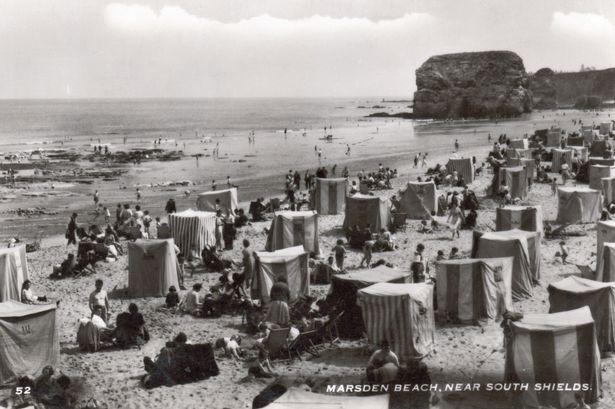

The fortunes of Grotto had turned around and it became a very popular venue. Its heyday being after the war on into the 50’s and 60’s when Marsden Bay was packed with day trippers and locals during the summer months. The pub was kept busy with the locals during the winter months.

During the boom period of the fifties a frequent visitor to the Grotto was the Irish tenor Joesf Locke. He would park his caravan in the Grotto car park and stay for a week or so. Local miners used to say that he loved the area and the people. On occasions if the drink had been flowing freely he would often entertain them with renditions of Hear my song, I’ll take you home again Kathleen, etc.

In the 1970’s like many other seaside resorts Marsden Bay and the Grotto were badly affected by the advent of cheaper foreign travel and the way people wanted to spend their leisure time. Gone were the days when a pot of tea and sandwiches on the beach was acceptable, people’s expectations were now higher. Both the Bay and the Grotto were now in decline.

In 1996 a further blow to Marsden Bay occurred when following a violent storm the arch of the iconic Marsden rock collapsed leaving two separate stacks and changing the face of the rock forever. In 1997 the authorities for ‘Health and Safety ‘ reasons blew up the smaller of the stacks.

Although not as grandiose as it once was the remaining stack still remains impressive.

In 1999 when Vaux pulled out of the brewing business the Grotto lay empty for sometime before being taken over by Tavistock Ltd. Since then it has had at least 2 different owners.

Today the Grotto is no different from any other British pub and with at least 20 pubs a week closing across the UK we are lucky that we still have this unique pub on our doorstep, this is in no small part to the current landlord Paul Simpson. Paul has diversified how the pub operates to maximise its potential in the current climate.

We wish Paul well in his endeavours to keep the pub open; the loss of the Grotto would be a huge blow to our heritage.

If you are thinking about visiting ring first and check opening times as these can vary 0191 4556060.

August 2015 update: The grotto as it is now under new ownership. We wish them every success in maintaining this unique public house.

B Cauwood 2014

References

Shields Gazette

Sunderland Echo

Tyne and Wear Museums

Newcastle Journal

breweryhistory.com/journal/archive/126/Swan

gerald-massey.org.uk/adams/c_autobiog10.htm

All copyrights acknowledged were known.

Copyright © 2013 Marsden Banner Group.

All rights reserved. Permission granted to reproduce text for educational use only (please cite source).